The Chipko AandolanBy women who decided to save trees

“The soil is ours. The water is ours. Ours are these forests. Our forefathers raised them. It’s we who must protect them.” A song from the Chipko Aandolan.

What was the Chipko Aandolan?

26 March 1973 is a red-letter day for the environment in India. The unique environmental movement, Chipko Aandolan, was started by women of Reni village of Uttarakhand (then a part of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh). 27 women, led by their compatriot Gaura Devi, decided to protest the commercial felling of trees in their village and adopted a unique strategy to stop the practice. They said the trees were the basis for their survival and that they were prepared to protest until tree cutting was stopped. They claimed first rights to forest produce, for which the survival of the forest was vital. They linked hands and formed tight circles around trees, thus not allowing for them to be cut. In Hindi ‘Chipko’ means ‘to hug’, ‘Aandolan’ means ‘revolution or movement’.

Nobody could have foreseen the impact on British colonial rule in India of one man, Mahatma Gandhi, making a fistful of salt. This seemingly simple act of defying an unreasonable law set a train of events in motion during India's struggle for freedom.

Similarly when women of one village in India decided to hold hands to form a simple human barricade to prevent trees from being cut, it snowballed into a wider worldwide movement for ecology.

Chipko Aandolan was a forest conservation, non-violent movement that soon spread with lightning speed around the world. The immediate impetus for the movement was a devastating flood of the river Alakananda in the Garhwal hills in 1970 which razed towns for nearly 320 kilometers from Hanumanchatti to Haridwar.

Deforestation over time had led to a lack of vegetation, firewood and fodder which were traditionally collected by women for their homes and cattle. With the cutting of trees the women now had to travel increasingly longer distances to collect these essentials. Also the lack of good water for drinking and agriculture due to less trees became more apparent with each passing year. The reduction of trees led to erosion of topsoil, and floods becoming more lethal than if there had been vegetation.

Big money overpowering the village small-scale industry

Inspired by the self-help Sarvodaya Movement of the Gandhian Jayaprakash Narayan, the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangh (DGSS) was established in 1964 to increase employment opportunities for villagers by setting up eco-friendly small scale industries using forest produce around Garhwal. DGSS faced several impediments due to British-era forest policies which only served to further the interests of rich contractors from towns who brought in their own labour from outside at the cost of employment for local residents. The locals had no say in the manner their resources were being used. In addition, the delicate ecological balance of the Garhwals was being strained with indiscriminate tree felling and construction activity.

The locals began to organise themselves to protest the large-scale logging contracts in the hills awarded to outsiders which did not benefit them. Awareness was also increasing of the negative impact of indiscriminate logging on the environment and the quality of their lives, especially after the flood. The villagers and the activists organised themselves to ensure all-night vigils at other locations where contracts had been awarded for tree felling without the villagers being informed. When these forms of protest did not have the needed impact of stopping logging, the DGSS and the villagers decided upon direct yet non-violent action.

The tipping point was when the government ordered the cutting of 2451 trees in March 1974 in the forests of Chamoli. The activists and the men of the village were called to a meeting elsewhere to decide upon the compensation amount. In the meanwhile a team of loggers arrived at the village, prepared to start cutting down the trees. A girl saw the preparations and alerted Gaura Devi who was head of the village women’s association Mahila Mangal Dal.

Gaura Devi and the other women of the village had had enough of the tree felling by then. They could no longer accept the exploitation of natural resources around them. The women decided to stage a protest that would not alienate sympathy nor harm their cause. They would protest the non-violent Gandhian way. Plus, they had the historical protest of the Bishnoi of Rajasthan as a beacon.

Environment activism in Indian history

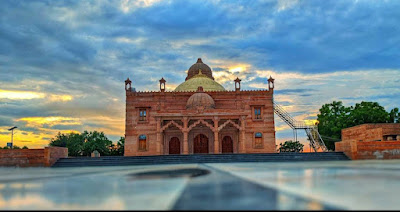

In on 11 September 1730 Amrita Devi led hundreds of her Bishnoi community to protect with their lives the sacred Kejeri tree. The ruler Abhay Singh of Marwar in Rajasthan wanted to cut a grove of these trees in the village of Khejarli in the district of Jodhpur to build himself a palace. When his men arrived at the village and demanded to be allowed to cut the trees, Amrita Devi Bishnoi and her compatriots refused. The king’s men tried bribing their way, insulting the Bishnoi even more with the implication that they would surrender their cherished values for greed of money.

Kaushal Bishnoi, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>,

via Wikimedia Commons

To stop the wanton destruction of their cherished trees Amrita Devi and the other women hugged the Kejeri trees in protest. That did not deter the king's men and they beheaded Amrita Devi and three of her daughters. Her last words are recorded as being, “A chopped head is cheaper than a chopped tree.” These stirring words soon became a rallying cry for the Bishnoi.

As the news of this killing spread all over Rajasthan, Bishnoi from 83 villages began to travel to Jahnad to do their part to protect the trees. The protest became bigger and bigger as the king’s minister would not stop his men from killing the Bishnoi. First the elderly Bishnois went forward to hug the trees and prevent the cutting. As they were killed the minister mocked the villagers saying they were sending forward only people who they thought were useless. In response, youngsters and children came to take the place of the elderly, and many were slaughtered. In all 363 Bishnoi gave their lives to a cause they fervently believed in.

This resistance, peaceful inspite of all odds, finally stirred Abhay Singh’s conscience. He travelled to Jehnad and personally begged for forgiveness. The village was renamed Khejarli after the sacred tree and is a place of pilgrimage for the Bishnoi.

11th September is today commemorated in India as The National Forest Martyrs' Day in honour of the Bishnois of Khejarli.

Environmental activism in the recent past

Gaura Devi went with 27 other women to the site to dissuade the loggers, but to no avail. When all the talking and subsequent shouting had died down, the loggers started to throw their weight and threatened the women with guns. That was when Gaura Devi and her fellow protestors decided to hug the trees by joining hands and forming human chains. They told the government officials that they would have to cut down the women too along with the trees, if they intended to proceed with the order. The women were prepared to protest until the bitter end. The stand-off continued all day and extended well into the night. The women did not budge.

By the next day, news of the womens’ protest had spread to the neighbouring villages and the crowds at the protest site swelled as more and more people gathered. Sympathy for the protestors was palpable, yet the situation continued to remain non-violent. This stand-off continued for four days after which the contractors left.

An influential way to protest for the environment

The impact of this action was such that the panel constituted by the Chief Minister of the state to look into it ruled in favour of the villagers. This form of protest was adopted by protestors all over the Garhwal region with much impact over the next five years. Within a decade the Chipko Movement protest methods were being used the world over for environmental causes.

Social impact of the Chipko movement

The initial Chipko Movement gave the impetus to several other social causes that needed a push up from the grassroots rather than top-down regulations. It brought women into the public arena to work for causes that impacted them personally. Some of the practices of the Chipko Movement were modified with women tying colourful strings to mimic rakhi around trees as protection bands to prevent felling.

Another social impact of the Chipko movement was that the supply of alcohol as a bribe to men in the villages by contractors to allow tree felling came to a stop. This practise had resulted in drunkenness, lack of money in families and other social problems. Involvement of women in this eco-system put an end to it.

The Chipko Movement showed that extractive and exploitative practices with regard to forest wealth are the major polluters, not poverty. Managing the environment is the only sustainable way to live.

Reference -

2. The Original Tree Huggers: Let Us Not Forget Their Sacrifice - Womens Earth Alliance